A brief word on the history of sight-singing

When I was a teenager, I noticed that there were people who were able to sing a melody that they had never heard before simply by reading from a page of sheet music. This made a deep impression on me. I was convinced that such people were born with some sort of supernatural ability and that mere mortals like myself might as well give up the notion of ever being able to do such a thing. When my mother told me that she had heard of a system whereby people could learn to sing from notes, I became very curious. But where could one find such a system?

I finally saw the light, when at the age of twenty, I began to study at the Berklee College of Music, in Boston, Massachusetts, USA. Later, I found out that I need not have traveled so far. This system is very old and universally known. It is called solfège.

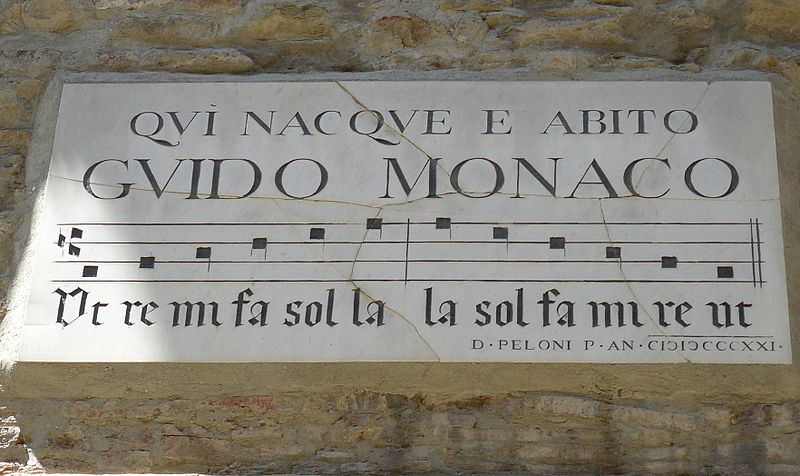

The system of solfège was invented nearly a thousand years ago by the same man who invented our note system. He was the Italian, Guido di Arezzo (ca. 995-1050).

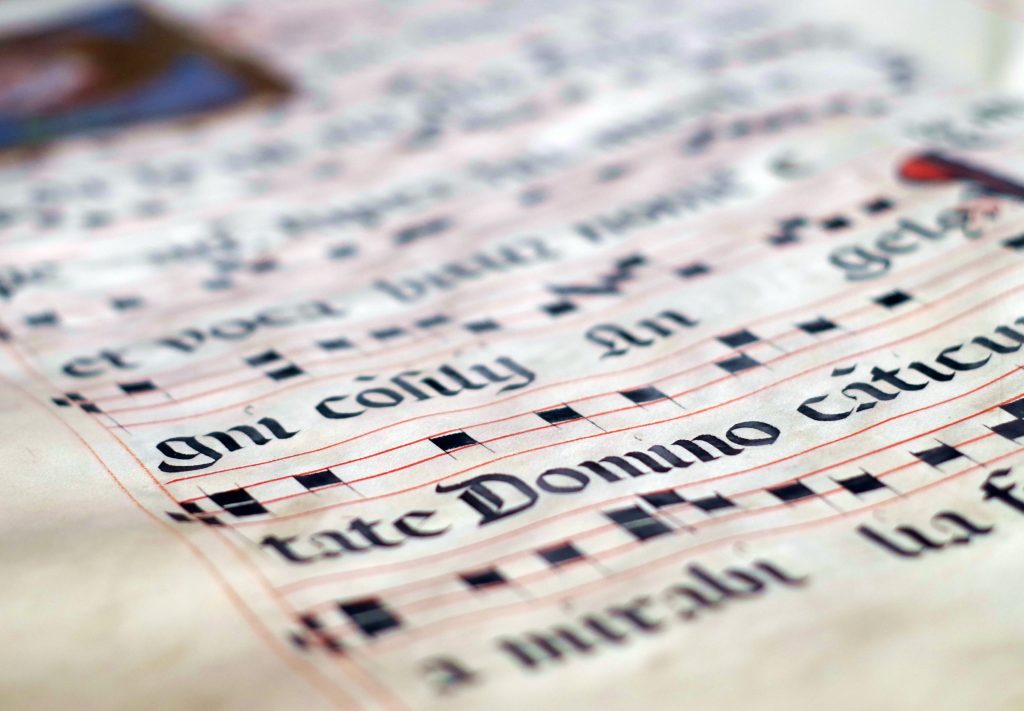

We don’t really know much about this remarkable man other than that he was a monk from a monastery in Arezzo, Toscana, and that he was known to be a wonderful teacher. The first that we hear of Guido is in 1029, when he is invited by Pope John the 21st. to demonstrate his by now famous teaching methods. Guido had two very interesting systems up his sleeve. One of them consisted of four horizontal lines on which could be placed some small squares, either on the lines or in the spaces between them. With the help of this system he could notate all of the churches melodies. The other system consisted of an old hymn from the 8th century that Guido had written a melody to. The text was as follows:

Ut queant laxis

Resonare fibris

Mira gestorum

Famulituorum

Solve pulluti

Labii reatum

Sancte Johannes

Guido had composed the melody in a major scale beginning the first tone of each line one step above the first tone in the preceding line. From this was derived the scale ut-re-mi-fa-sol-la. Now, having learned Guido’s melody by heart, the student could always find the tone mi or fa in relation to the tonic (the first tone of the scale). But that wasn’t all. Guido claimed that with the help of these two systems he could teach a person to sing from notes in one month. A new era had begun. The pope was impressed. He knew that for hundreds of years the church had tried hard to get the melodies on paper. Now, this man stood in front of him with a system in hand whereby not only all the melodies could be written down, but people could learn to read them fairly easily. “I propose that you assume the position of Bishop”, said the Pope. But Guido was deep into the world of music and did not want the many obligations that would weigh heavy on the shoulders of a bishop. Instead he chose to continue teaching and doing research, which we should probably be very grateful for to this day.

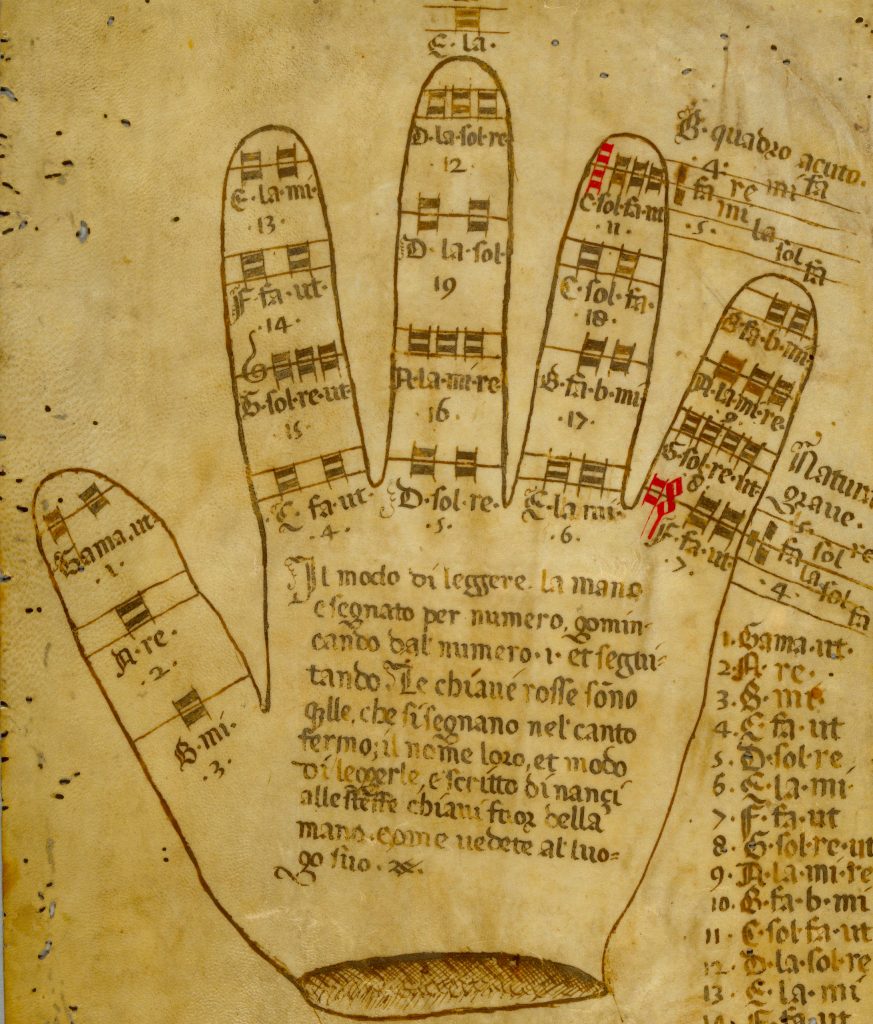

Guido had many other inventions. One of them was “the Guidonian Hand”, a system in which various places on the palm of the hand and on the fingers represented different syllables in the solfège exercise. The teacher could now, by pointing to his left hand, train the choir and the students in little melodies or difficult “jumps”.

After the death of Guido in 1050 there was no one who was able to – or who dared – make improvements to the system. For centuries the ut-re-mi-fa-sol-la scale was used for singing, until in the 16th century it became the ”do-re-mi-fa-so-la-ti-do” – the major scale that we know today. The pure minor scale was always sung from the “la”: “la-ti-do-re-mi-fa-so-la” – the pure minor scale.

This is a sort of switching around of the major scale. In our day and age, where there is a lot of consciousness as to the use of scales, there is a tendency to let the “do” be the tonic (the first tone of the scale), giving the following appearance to the minor scale: do-re-me-fa-so-le-te-do. It is still a pure minor scale, but now it has the same order and nearly the same names as in the major scale, just with a lowered 3rd, 6th and 7th step.

In theory it is all very simple. Now let’s get to practicing!